Organisational layering: a perspective on organisational development

In a recent article, ” Strategy is Evolution”, I introduced the idea of strategic layering. This idea states that strategy is not sequential but layered in time. Previous strategic choices have strong impact on the scope and nature of a company’s future strategic room to manoeuvre. In this sense, an organisation is never free of its strategic history. And as I argue in that particular article, there is enormous power and value in a strong relationship with an organisation’s strategic past.

In my opinion, this idea of layering is also, and perhaps even more strongly so, applicable to organisations. Not from a strategic perspective, but from the perspective of organisational development. Because in the (further-) development of our organisations, the organisational history of a company plays a major role. That history, just like the strategic history of a company, does not disappear the moment we decide that adjustments to the organisational concept are needed. In fact, that history is highly relevant at that moment.

In this article, I argue that successful organisational development perceives the next phase of the organisation’s development as an addition, an add-on to what is already there and not as a replacement of what was there. This in contrast to the common view within change management, where the starting point is replacement and not addition.

Change management: the meallable organisation par excellence

The history of organisational thinking is permeated with the social engineering, the social construction principle. The organisation as a construct that can be engineered and designed. A set of functions, roles, procedures and hierarchy aimed at the execution of strategy. Structure follows strategy. In the article “Why we should finally come to alternative organisational models and not only think about it” by my colleague Anna-Leena Haarkamp, this engineering perspective on organisations is described in detail. Within this principle, we strive for and believe in such a thing as “the ideal organisation”, which is often defined in functional terms (a sum of tasks and responsibilities within a certain hierarchy).

And according to that principle if the existing form of organisation proves to have certain shortcomings, a new ideal form will have to be designed and replace the old form. We replace the old form with a new one. Whereby the old is often seen as inadequate, negative or even wrong. We have to adapt the organisation.

An organisational concept consists of the sum of people, competencies, culture, structure, processes, procedures and tools that govern the functioning of the organisation. In this sense, I am closely aligned with McKinsey’s 7-S model.

In the philosophy of organisational engineering, this migration can be managed and controlled. The corresponding process is called CHANGE MANAGEMENT for a reason. In this line of thinking, we first design the new ideal organisational form, then examine which employees fit in well within that form, train and educate those employees who can migrate to the new organisation and then, apart from some technical ICT adjustments, assume that everything works smoothly. Reaching the new ideal form fully functional is a matter of course. Perhaps my description comes across as somewhat of a simplified representation of affairs, but in essence this is how we predominantly approach organisations and organisational change.

Adding works better than replacing

I am in favour of a different way of thinking. One in which we do not think in terms of replacing, but of improving. A view in which we let go of the idea that the existing organisational form should be replaced by a new, better one. A way of thinking in which we see our organisational history as valuable not as replaceable. After all, it was the form that brought us our current success. In a next phase with new challenges, that form may need adjustment, but in my view the appropriate metaphor is development not change, and certainly not replacement. Because for one, what was and what made us successful in the past is not gone the moment we we decide that an adjustment is required. You cannot erase your organisational history.

An organisation is more than the purely rational functional construct of tasks, roles and hierarchy aimed at the execution of strategy. It is just as much a sum of people, of competencies, of a culture, of relationships, formal but especially informal. An organisation is tangible as in the rational functional construct of tasks, roles and hierarchy, but is above all intangible as in a network of people, culture, competencies, relationships and relations. This intangible side of organisations is an important part of our organisational history. And this intangible side of organisations cannot be erased. It forms the social construct that binds the organisation and its people, it forms the human side of an organisation. It is the intangible side of organisations that can only be successfully developed and not changed. Let alone replace.

A good example of this view of organisational development is the merger of Perfetti and Van Melle. Two totally different companies. One innovative, lively and creative. The other ordered, structured, procedural and efficient. The integration process of these two companies departed from “the idea of adding”. “They have something that we cannot and we can do something that they cannot.” Complementarity. The fact that these two companies were able to integrate so successfully is primarily explained by the basic idea underlying the integration process: to ADD. COMPLEMENTARITY.

If you want to know more about this, watch the interview with Ko van Belois at www.vibrant-thinking.org/interviews

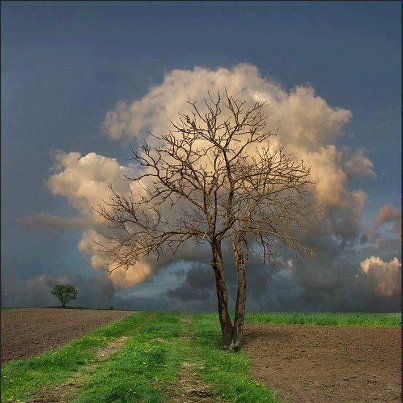

So, within the development perspective, we accept our organisational history. And organisational development then becomes the process of adding to our history. As said, that history is not gone just because we think something has to change. In short, in the development perspective, as opposed to the change perspective, we add to what is there. We start from organisational stratification, layers of organisation. And that stratification, that layering gives the organisation its strength.

An addition always brings tension

Something new always creates tension. Preferably positive tension. And so, it is with organisational development. If a changed context or our ambitions demand that we further develop our organisation, that we add something to our organisation, that our organisation goes through a certain development, this always creates tension. Because it is something new, something that does not yet exist within our history. And the great challenge of organisational development is to deal with this tension. To use and accept this tension positively as part of a development process. Because, the reasoning goes: if we add to our history, if we want to enrich our history by adding something, then the tension between what was and what will be added is a logical part of that process. No development without tension. The acceptance of this tension as a source of positive energy is the basis for successful organisational development. We add a chapter to the history of the company. All the chapters in that history are valuable. We do not change because there is a mistake in our history, we develop because we want to enrich our history. To add to our history. Layering of organisation.

In the comparison between our organisational history and its renewal, we discover the nature of the tension between existing and new. It is the nature of this tension that is indicative of the development challenge and scope. From a development perspective, it is desirable to explicitly name, describe the nature of this tension. So that everyone knows what is in store for us. Knows about the changes coming our way. And so that everyone can experience these as a logical part of our development path and not as a replacement of the past. In that sense, explicitly naming and describing the tension between existing and new can only contribute to a better understanding of the development challenge. In the hope that understanding will lead to enthusiasm. Healthy tension.

The reverse is also true. Not explicitly naming the nature of the tension curve, but introducing the intended development, leads to confusion and resistance. One could say: An explicit tension curve hopefully leads to explicit support and momentum, but an implicit tension curve by definition leads to explicit resistance and distrust.

Not only is there a gain to be made by explicitly naming the intended development and the corresponding tension curve. There is also a great risk in not explicitly naming the development step and the tension curve. All the more reason for an open and transparent approach to organisational development.

Layers of organisation

The history of an organisation cannot be erased. The tangible and intangible aspects of an organisation have a certain durability. A certain continuity over time. That is why a development perspective on organisations is more appropriate than a change perspective. And within that development perspective, we add to history. The nature of the tension between past, present and future determines the direction of the development challenge. This creates valuable “layers of organisation”.